|

|||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| QUICK VOTE | ||||

|

|

||||

| NEW FROM COMPUTER GRAPHICS WORLD | ||||

|

CGW Online awarded TopTen award on TenLinks.com |

||||

| PENNWELL CONNECTIONS |

||||

|

|

||||

|

| ||

| Moving to the Beat | ||

|

A performer creates music-driven visualizations in real time | ||

|

By Karen Moltenbrey | ||

No performer, past or present, has created moving music in quite

the same manner as twenty-first century instrumentalist Mobius 8,

whose cutting-edge sounds are being used to generate real-time

interactive 3D visual effects. John Laraio, known as Mobius 8,

displayed this unique music video capability during his live stage

performances with pop rock band 'NSync during its 2001 global tour.

"The ability to translate my music into a visual display gives me

the power to actually play the graphics, lights, and video for the

audience," says Laraio. | ||

|

The ensuing 3D imagery is rendered in real time, so the visuals are in harmony with the music, and projected onto a large LED screen above the stage. "The result is a harmonious visual confirmation for the mind's eye, connecting what you see on the screen with the sounds you are hearing. Subsequently, the audience receives a more amplified and fulfilling experience," adds Hotz. | ||

| Sights and Sounds | ||

|

Laraio conceived the idea of controlling invisible frequencies of light so they respond to motion and produce wondrous sounds. Yet it was the technical wizardry of Hotz, a record producer, engineer, musician, and inventor, who linked those sounds to imagery through Zuma. "I did not know of any 3D graphics engine that allowed every parameter and every aspect of a visual to be generated in absolute real time," Hotz says. "So I put a team together to explore whether current hardware technology was mature enough to accomplish this type of real-time manipulation within the 3D world." Hotz's approach was to treat every element within the 3D graphics world as if it were an object in the musical universe-in essence, having the imagery follow the same cycle as musical "envelopes," where a sound rises and falls (known as attack, decay, sustain, and re lease). "So if I have a 3D object, such as a cube, and I want to expand its size, I do that by manipulating the sound through visual envelopes," he explains. | ||

This concept became tangible when 3dMaxMedia (San Jose, CA) created Zuma, a commercially avail able real-time graphics engine that incorporates WildTangent's Web Driver technology, typically used for Internet gaming and 3D Web development. "I looked at every product that was available for real-time manipulation of graphics. There are some amazing game engines, but most of them require a tremendous amount of system memory, which wasn't practical since we had planned to make Zuma available over the Internet," says Hotz. | ||

|

Although the WildTangent Web Driver played a key role in creating Zuma, the majority of the technology had to be invented from scratch by Hotz. "[At the time] no one had really pursued the type of manipulation in the graphics world that we wanted to accomplish through audio," Hotz notes. | ||

| Creating a Scene | ||

|

Hotz created the 3D images used for the concert tour using Zuma's built-in editor, although Zuma accepts other 3D software and image formats, including Discreet's 3ds max. The parametric models were derived from algorithms generated inside of Zuma, which resulted in pure polyhedral classes of objects. | ||

|

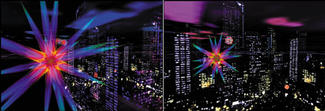

These 3D images, created in 3dMaxMedia's Zuma software, spring to life as they move and morph in harmony with the music. The result is an engaging experience of coordinated sights and sounds. Images courtesy Jimmy Hotz and 3dMaxMedia. "These classes seem to be infinitely variable yet maintain a magical symmetry," says Hotz. "The symmetrical beauty is de rived from the pure mathematical nature of the models, which makes them lightweight and highly optimized for the demanding task of real-time manipulation." | ||

|

The geometric objects were then textured with a variety of images, including video footage residing on the computer hard drive, real-time video coming into the Firewire port, and still images such as those edited in Adobe Systems' Photoshop. Ac cording to Hotz, the textures can be applied to the entire object or to a single face of the object, whether it's a cube, flat plane, sphere, or something Hotz de scribes as a "unique spirit-like object that defies explanation." | ||

|

When composing the scenes, Hotz first created the background object, typically a plane or a sphere, which he then textured with a nature scene or star field. In the foreground, he created another object, such as a torus, that could be spun and viewed from various angles. | ||

"Most of the interesting manipulation is done with the foreground objects, so that's where you can really achieve some interesting results by using different textures, such as a rainbow gradient, video clip, or animation," says Hotz. "You can take traditional pictures of just about anything, place them on a kaleidoscope object, connect a few manipulators, and the outcome is amazing." | ||

|

One challenge was choosing the types of scenes for the concert that would be aesthetically pleasing in the large concert arenas. "Things can look totally different on a computer screen than they do on one of the world's largest LED video screens in a giant stadium venue," says Hotz. To resolve that issue, he visited the Louisiana Superdome, where 'NSync and Mobius 8 practiced prior to touring, so he could tweak the original images and scenes based on their appearance in the larger setting. | ||

|

During the concert tour, the images were projected onto one of the largest LED screens made. Driving the visualizations was a 1.4ghz Pentium 4 with an Nvidia GeForce 2 card, which automatically rendered the images to the required resolution. Typically, resolutions of 1280-by-1024 or 1024-by-68 pixels are used, but for the NSync tour, the images were rendered at 640-by-480 pixels because the video mixer was converting the graphics to this resolution. | ||

|

"At first I wondered if this resolution would be high enough to look good on such a large screen, but the venues were so huge that most of the audience was seated far enough away to not perceive the individual pixels, and the images looked great," says Hotz. | ||

| A Manipulator | ||

|

Once Hotz created the basic images, he programmed the properties that would be manipulated, from opacity to proportion to cam era angle to lighting (brightness, color, position, etc.). "Every possible image parameter or primitive can be programmed for real-time manipulation," he says. "In one scene, I created a torus and devised a formula so the object could be manipulated in such a way that the result was something that looked like a living creature rather than a doughnut. Through this type of manipulation, you are no longer limited by an object's pure geometry." | ||

|

Two highly modified geometric models travel in front of the camera as it sweeps through this cityscape. The objects change shape, size, and opacity as they twist and turn in response to the music and control gestures of Mobius 8, which also manipulate the camera and lighting. The parameters were then linked to a controller, which manipulated the object in real time, at about 30 frames per second. In the Mobius 8 performances, the audio frequency is generated by the musician's Hydra and MIDI (musical interface digital interface) through his gestures, which act as the controllers. Therefore, as the amplitude of a particular audio frequency rises and falls, the value of the parameter to which it is assigned changes and transforms the object, thereby altering the object's appearance in real time. So, if the object's opacity is programmed to respond to a specific audio frequency, then the object will grow in visibility as that frequency's amplitude intensifies, and be come less visible as the frequency's am plitude decreases. | ||

|

"This is different from a typical key framed animation because each variable has its own time domain that can be altered on the fly while it controls a sequence of action. A keyframed sequence has a specific timeline, whereas this type of movement can be controlled and changed at the very moment it is happening," explains Hotz. "That's why the objects created with Zuma behave like living creatures-every aspect is constantly moving, growing, changing, evolving." | ||

| Real-time Effects | ||

|

According to Hotz, manipulating imagery in real time positively affects the creative process. Since the changes occur so quickly, there is a direct link back to the mind that connects the visual feedback to a specific gesture or sound. "It takes the creative process to a whole new level," Hotz says. "You no longer have to think about an action, make static frames, and have the computer interpolate the animation over time before seeing the result. I can change my approach based on immediate feedback if I see that something especially interesting is occurring." | ||

|

Although dramatic changes can be made to the images, the underlying thread of the visual content remains intact. "[The visuals] at every concert are different in the same way that live music differs each time a song is played live," says Hotz. "It can vary greatly if the musician plays a tune far differently than he usually does. The musician is in control of the visualizations. And the result is serendipity." | ||

|

Some musicians write down notes one part at a time and then have other musicians perform the piece along strict guidelines without much improvisation, which is similar to how traditional 3D graphics are created. Others simply pick up a guitar and create songs as the inspiration leads them. "Zuma enables a visual artist to create and improvise in real time, which is how these graphics were created," Hotz explains. This type of creative ability is not limited to live stage performances. In fact, Hotz predicts that the technology soon will spur a whole new genre of prerecorded music videos. | ||

|

Although millions of people witnessed Mobius 8's visualization performances during the concert tour, few probably realized that the musician was controlling the imagery in real time. "I don't think people appreciated what was happening," notes Hotz. "It was a breakthrough event in the music world. Mobius 8 is the first of what will be a whole new type of performance artist." | ||

|

And based on reviews of the concert tour, it's obvious that

Mobius 8's concert performances were quite moving. | ||

|

Karen Moltenbrey is a senior associate editor at Computer Graphics World. | ||

| Computer Graphics World November,

2001 Author(s) : Karen Moltenbrey | ||

| CURRENT ISSUE | ||

|

December 2002  |

||